Fern Sherwood

Fern SherwoodTuition fees are rising for undergraduate students at universities in England for the first time in eight years.

Students from the UK will pay £9,535 per year in 2025-26, a rise of £285.

The National Union of Students called it a “sticking plaster” for struggling universities, while Universities UK, which represents 140 institutions, said it was “the right thing to do”.

The BBC has spoken to two friends from the heart of rural Devon, who met at Exeter College while studying for a T-level in business management and administration.

They have since gone their separate ways, with one in his first year at uni and the other working nine-to-five.

What does the hike in fees mean to them, and do they think university is value for money?

Isobel, 18: ‘I’m even happier I’m not going to uni now’

Handout

HandoutDespite claiming she has “never really been academic”, Isobel says she assumed she would end up at university throughout her time at secondary school.

It was only when she arrived at college that other opportunities became apparent. Instead of taking the traditional three A-levels, Isobel chose a T-level course which provided work experience alongside her studies.

It did not take long for her to realise university was not for her, and Isobel did not attend any open days.

Now embarking on a new job in a legal support role, she says she is “even happier with her decision” with university fees on the rise.

“I didn’t want the debt,” she says.

“By the time everyone else comes out of university, I’ll have some savings behind me, I’ll be embedded within a company, and hopefully will have gained some qualifications in my job.”

The Student Loans Company says graduates in England currently leave university with average debts of £48,470.

In 2023, loan terms were increased from 30 to 40 years and repayment threshold salaries were lowered, from £27,295 to £25,000, meaning more graduates will be repaying their loans, for longer.

Isobel says she is one of just two people, among a group of 12 friends, who is not going to university.

For now, many of her friends have taken gap years, but Isobel says she worries about “fomo [fear of missing out]” when they eventually leave for university, and are out partying on a Wednesday night.

“By the time they graduate, I think I will feel a bit envious, too, that they’re getting these lovely certificates for all the hard work they’ve done – while I will have been working hard but won’t get a big celebratory day,” she says.

Sam, 18: ‘I track my Monzo like a hawk’

Handout

HandoutUniversity was always part of the plan for Sam, who wants to set up his own marketing agency, like his dad.

Despite fees going up, Sam says he thinks his business degree at Bath Spa University has been “incredible” value for money so far, when he considers all the extras available to students.

“At college, I can go to see the therapist we have on campus to have a chat, I can go into the library and use all these online resources,” he says.

Sam is paying for his tuition – which in his first term includes 12 hours of contact time per week – with a student loan.

The debate over whether some university courses provide value for money was a major topic during the last general election, after the previous Conservative government said it would scrap some “rip-off” degrees.

Previously, some students have complained that a lot of their contact time still remains online, long after Covid.

But Sam believes his course still represents good value, because each hour of lectures or seminars also comprises three hours of external study.

He is also benefiting from the wider student experience. Speaking from his student halls, he says he has met “some of the kindest and loveliest people”, and is enjoying exploring a new city.

But Sam says there is “always stress” about money, adding that he watches his bank account “like a hawk”.

“I have friends who have had to ask their parents for money – and I’ve had to calm them down,” he says.

“They think, ‘I’ve failed as a kid, I’ve had to take more money off my parents – I’m not sustaining myself.’ It’s damaging to their mental health.”

Responding to the government’s announcement on fees, one personal finance expert said parents of young children should start saving now for their university years.

Sarah Coles, from financial services firm Hargreaves Lansdown, said parents of children heading to university should “be clear about what level of financial support they can expect from you”.

Sam says he feels lucky to have a Lidl on his doorstep, and spends roughly £20 on his weekly shop.

He also pays for his journeys to and from campus.

After a busy freshers’ week, he says going out is now limited to a couple of pints at the pub once or twice a week.

‘Massively beneficial’

Sam’s rent, at roughly £8,500 for the year, is being paid for by his parents. He is also given a monthly allowance of £250 to support his living costs.

Next year, as well as increasing domestic tuition fees, the government is also increasing the caps on maintenance loans – to help students better afford their living costs.

Caps on loans are increasing from £10,227 to £10,544 for students living away from the family home outside of London, and from £13,348 to £13,762 for those students living in London.

But personal finance expert Martin Lewis says maintenance loans are still not large enough to support students who are unable to access additional help from their parents.

Sam’s parents have set up their home as an Airbnb to help Sam and his older sister through university.

His dad, David, says they were determined to “find a way” to make it happen.

David says he is “a believer in paying the going rate”, as long as students are getting value for money in terms of access to their lecturers and the same extra-curricular opportunities, like trips and placements, that they would have had before Covid.

But he says if costs went up further there would have to be a “tough conversation about what we can do” to financially support the children.

David says he hopes there will be more value to Sam’s time at university than just a degree.

“In terms of the full uni experience, what I’m seeing is massively beneficial for him,” he says.

“Sam could come out with a great business degree, and, yes, it will give him a step down that path – but will it define who he is in 10, 15 years? I hope not.

“I hope he comes out of it thinking that was a great time in his life, that he met loads of really cool people who are friends for life.”

What’s next for universities?

The government hopes that increasing tuition fees will put universities on a “firmer financial footing”.

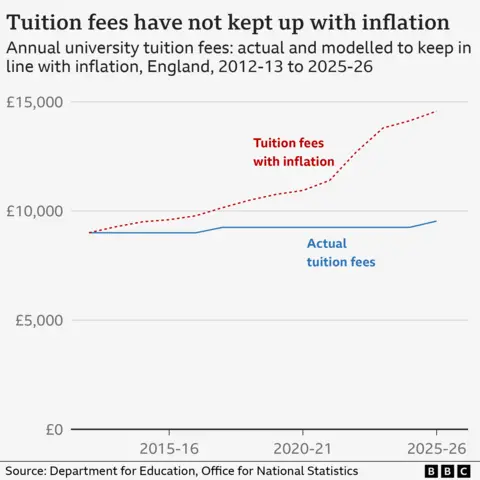

Since a boom in university spending after fees tripled to £9,000 in 2012, they have only increased by £250.

That has left universities increasingly reliant on international students, who pay higher fees.

But stricter visa rules mean the number of overseas students applying to UK universities is falling.

The latest tuition fee increase is also significantly less than the £12,000-£13,000 that universities have argued is sufficient to meet the current cost of teaching.

The government previously told universities to get their own finances in order amid calls for potential bailouts and warnings that 40% of universities could be in a financial deficit this year.

In general, research by the Higher Education Statistics Agency suggests most graduates can expect to earn more than non-graduates.

Moreover, the Save the Student money advice website said the latest rise in tuition fees would make “little difference to overall levels of student debt, and will have no impact whatsoever on the amount a graduate repays each month”.

But borrowing more will, inevitably, mean students leave university with more debt.

The government’s latest announcement also only stipulates fees and loans in the 2025-26 academic year. Vice-chancellors and students alike will want to know what the government’s plans are beyond that.

Universities will hope they can convince the next generation of prospective students that they are still worth the money.