By Flora Drury, BBC News

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen it comes to planning a holiday, Afghanistan is not at the top of most people’s must-visit lists.

Decades of conflict mean that few tourists dared step foot in the Central Asian nation since its heyday as part of the hippie trail in the 1970s. And the future of whatever tourism industry had survived was thrust into further uncertainty by the Taliban’s return to power in 2021.

But a quick scroll through social media suggests that not only has tourism survived, it has – in its own, extraordinarily niche way – boomed.

“Five reasons why Afghanistan should be your next trip,” gush the delighted influencers, their cameras sweeping across glistening lakes, through mountainous passes and into colourful, busy markets.

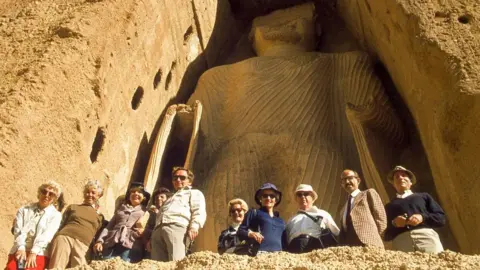

“Afghanistan hasn’t been this safe in 20 years,” others declare, posing next to the vast chasms left behind by the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas more than 20 years ago.

Behind the sunny claims and glamorous videos are questions about the risks these travellers are taking, and exactly who this burgeoning industry is truly helping: a population struggling to survive, or a regime keen to shift the narrative in its favour?

“It is very ironic to see those videos on TikTok where there is a Taliban guide and Taliban official giving tickets to tourists to visit the [site of the] destruction of the Buddhas,” points out Dr Farkhondeh Akbari, whose family fled Afghanistan during the first Taliban regime in the 1990s.

“These are the people who destroyed the Buddhas.”

‘It’s just raw’

The list of countries visited by Sascha Heeney do not, on first hearing, sound like ideal holiday destinations – places many will be more used to reading about in the news.

But then, that appears to be exactly why Heeney, and thousands more like her across the globe, picked them out: off the beaten track, as far away from a five-star resort as you can get – and therefore, almost entirely unique.

So perhaps it is not surprising she was won over by Afghanistan.

“It is just raw,” says the part-time travel guide from Brighton, UK. “You don’t get much rawer than there. That can be attractive – if you want to see real life.”

What do the Taliban get out of it? After all, they have a reputation for being deeply suspicious, hostile even, towards outsiders, particularly Westerners.

And yet here they are, posing – if slightly uncomfortably – alongside the tourists, guns on show, their bearded faces potentially about to go viral on TikTok (banned in the country since 2022).

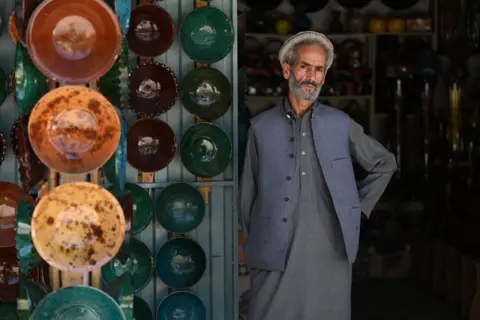

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt one level, the answer is simple. The Taliban – largely isolated internationally, under widespread sanctions and prevented from accessing funds given to Afghanistan’s former government – need money.

The tourists – whose numbers have crept up from just 691 in 2021 to more than 7,000 last year, according to AP news agency – bring it.

Most seem to join one of myriad tours offered by international companies, providing a peek at the “real Afghanistan” for a few thousand dollars a trip.

Mohammad Saeed, the head of the Taliban government’s Tourism Directorate in Kabul, said earlier this year that he dreamed of the country becoming a tourist hotspot. In particular, he revealed, he was eyeing up the Chinese market – all with the backing “of the Elders”.

“All they want to do [with tourism], it’s good,” says Afghan tour guide Rohullah, whose smiling face has been shared dozens of times by happy clients since he started leading groups three years ago.

“Tourism creates a lot of jobs and opportunities,” he adds – and he should know.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAfter what he refers to as “the change” in 2021 – when the Taliban seized power as the US pulled out – he was offered a job as a tour guide by a friend. Before that, he had spent eight years working for the Afghan finance ministry.

And he hasn’t regretted it. Tour groups like Heeney’s need drivers and local guides, and with tourist numbers continuing to rise, there is no shortage of work.

It is not surprising then to find groups of young men – and they are all men – attending Taliban-approved hospitality classes in Kabul, hoping to take advantage of the burgeoning industry.

“We expect much for this year,” Rohullah says. “This is a peaceful time – it was not possible to travel to all parts of Afghanistan before, but for now, it really is possible.”

The killing of three Spanish tourists and an Afghan at a market in Bamiyan in May by the Islamic State-affiliated ISK militant group stood out for being unusual because it targeted foreigners.

The British Foreign Office continues to advise against all travel to the country, which remains a target for attacks. ISK carried out 45 in 2023 alone, according to the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point.

Of course, part of the reason for Afghanistan’s increased security now is that during the 20 year war which engulfed the country after the US invasion, the Taliban themselves were responsible for much of the violence.

Take – for example – the first three months of 2021, when the UN attributed more than 40% of the 1,783 civilian casualties recorded to the Taliban. It wasn’t just the Taliban though. The same report noted US-led Afghan government forces were responsible for 25% of the casualties in the same period.

‘Know the rules and learn the game’

What is perhaps more surprising is that Heeney and two other members of the group she led for Lupine Tours earlier this year were women – and they were far from the only ones. Young Pioneer Tours – which has long experience of organising holidays to North Korea and other off-grid destinations – even runs exclusively female trips to Afghanistan. Rohullah has guided female solo travellers “without any issues”.

The Taliban’s strict rules for their own female population – which has seen them forced out of the workplace, out of secondary education and even out of the Band-e-Amir national park, a stop on many of the international tours on offer – do not preclude female tourists visiting.

It does mean that “women and men have different encounters” in Afghanistan, acknowledges Rowan Beard, who has been bringing groups to the country since 2016. It is not necessarily a bad thing, he argues.

“Men cannot speak with women; women can,” he explains. “Our female tourists had the opportunity to sit with a group of women and hear from them about their experiences, and further insights into the country.”

But everyone needs to follow the rules put in place. Heeney and her group were briefed in advance of what would be required in order to meet those rules, including on how they dressed, how to act and who they could, and couldn’t, talk to.

The Taliban – ever-present, watching from the sidelines with their guns – were among those who did not speak to Heeney or the female members of her group. She didn’t begrudge it.

“You have to kind of know the rules and learn the game,” she explains.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor Heeney, speaking with the women – who were “incredibly happy” the group was visiting – was a highlight on a tour where the “absolutely lovely”, generous and welcoming people of Afghanistan stood out.

In videos posted on social media, the women are noticeably missing from vibrant street scenes – a fact glossed over by one visitor, who declares people shouldn’t worry, they are just inside doing what women around the world love to do: shop.

‘Whitewashing our suffering’

Watching these slick videos from outside Afghanistan, some are left with a bitter taste.

“[Tourists think] it is just this backward part of the world, and they can do whatever they want – we don’t care,” says Dr Akbari, now a postdoctoral researcher at Monash University in Australia.

“We just go and enjoy the landscape and get our views and our likes. And this hurts us a lot.”

It is, she adds, “unethical tourism with a lack of political and social awareness”, which allows the Taliban to gloss over the realities of life now they are back in power.

Because this is, arguably, the other value of tourism to the Taliban: a new image. One which doesn’t highlight the rules controlling the lives of Afghan women.

AFP

AFP“My family – they have no male guardian – cannot travel from one district to another district,” Dr Akbari points out. “We are talking about 50% of the population who have no rights… We are talking about a regime which has installed gender apartheid.

“And yes, there is a humanitarian crisis: I’m happy that tourists might go and buy something from a shop and it might help a local family, but what is the cost of it? It is normalising the Taliban regime.”

Heeney admits she did have a “moral struggle” over the Taliban’s position on women before she visited.

“Of course, I feel very strongly about their rights – it crossed my mind,” she says. “But then as a traveller… I think countries are deserving to go to, and be listened to – we have a skewed idea. I like to see with my own eyes. I can make my own judgment.”

Beard argues for letting people “make their own conclusions rather than there being a one-size-fits-all answer to the experience women have in the country”.

The overly positive view shared by some on social media can definitely be seen as problematic, says Marina Novelli, professor of marketing and tourism at Nottingham University School of Business.

“I would be very wary of the sensationalisation of a destination,” she says, explaining that some may “paint an image that is naïve”.

“Sometimes travellers also want to send a positive message – but that does not mean that problems [aren’t still there].”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBoycotting is also not the way forward, argues Prof Novelli, who sits on an international tourism ethics board.

“I find that problematic – it isolates these countries even more.”

It also opens up a question over where to draw the line – there are plenty of tourist destinations in the global north which have governments with questionable practices, she says.

However, the potential for benefit is also worth considering: in Saudi Arabia, she says, a growing tourism industry has led to a widening role in society for women.

“I think tourism can be a force for peace, for cross-cultural exchange,” Prof Novelli says.

That potential though does not make it easier for women like Dr Akbari, and her family and friends in Afghanistan.

“Our pains and our sufferings are being whitewashed,” she says, “brushed with these fake strokes of security the Taliban want.”