BBC

BBCIn January 2015, Abdullah, the 90-year-old king of Saudi Arabia, was dying in hospital. His half-brother, Salman, was about to become king – and Salman’s favourite son, Mohammed bin Salman, was preparing for power.

The prince, known simply by his initials MBS and then just 29 years old, had big plans for his kingdom, the biggest plans in its history; but he feared that plotters within his own Saudi royal family could eventually move against him. So at midnight one evening that month, he summoned a senior security official to the palace, determined to win his loyalty.

The official, Saad al-Jabri, was told to leave his mobile phone on a table outside. MBS did the same. The two men were now alone. The young prince was so fearful of palace spies that he pulled the socket out of the wall, disconnecting the only landline telephone.

According to Jabri, MBS then talked about how he would wake his kingdom up from its deep slumber, allowing it to take its rightful place on the global stage. By selling a stake in the state oil producer Aramco, the world’s most profitable company, he would begin to wean his economy off its dependency on oil. He would invest billions in Silicon Valley tech startups including the taxi firm, Uber. Then, by giving Saudi women the freedom to join the workforce, he would create six million new jobs.

Astonished, Jabri asked the prince about the extent of his ambition. “Have you heard of Alexander the Great?” came the simple reply.

MBS ended the conversation there. A midnight meeting that was scheduled to last half-an-hour had gone on for three. Jabri left the room to find several missed calls on his mobile from government colleagues worried about his long disappearance.

For the past year, our documentary team has been talking to both Saudi friends and opponents of MBS, as well as senior Western spies and diplomats. The Saudi government was given the opportunity to respond to the claims made in the BBC’s films and in this article. They chose not to do so.

Saad al-Jabri was so high up in the Saudi security apparatus that he was friends with the heads of the CIA and MI6. While the Saudi government has called Jabri a discredited former official, he’s also the most well-informed Saudi dissident to have dared speak about how the crown prince rules Saudi Arabia – and the rare interview he has given us is astonishing in its detail.

By gaining access to many who know the prince personally, we shed new light on the events that have made MBS notorious – including the 2018 murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi and the launch of a devastating war in Yemen.

With his father increasingly frail, the 38-year-old MBS is now de facto in charge of the birthplace of Islam and the world’s biggest exporter of oil. He’s begun to carry out many of the groundbreaking plans he described to Saad al-Jabri – while also being accused of human rights violations including the suppression of free speech, widespread use of the death penalty and jailing of women’s rights activists.

An inauspicious start

The first king of Saudi Arabia fathered at least 42 sons, including MBS’s father, Salman. The crown has traditionally been passed down between these sons. It was when two of them suddenly died in 2011 and 2012 that Salman was elevated into the line of succession.

Western spy agencies make it their business to study the Saudi equivalent of Kremlinology – working out who will be the next king. At this stage, MBS was so young and unknown that he wasn’t even on their radar.

“He grew up in relative obscurity,” says Sir John Sawers, chief of MI6 until 2014. “He wasn’t earmarked to rise to power.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe crown prince also grew up in a palace in which bad behaviour had few, if any, consequences; and that may help explain his notorious habit of not thinking through the impact of his decisions until he had already made them.

MBS first achieved notoriety in Riyadh in his late teens, when he was nicknamed “Abu Rasasa” or “Father of the Bullet”, after allegedly sending a bullet in the post to a judge who had overruled him in a property dispute.

“He has had a certain ruthlessness,” observes Sir John Sawers. “He doesn’t like to be crossed. But that also means he’s been able to drive through changes that no other Saudi leader has been able to do.”

Among the most welcome changes, the former MI6 chief says, has been cutting off Saudi funding to overseas mosques and religious schools that became breeding grounds for Islamist jihadism – at huge benefit to the safety of the West.

MBS’s mother, Fahda, is a Bedouin tribeswoman and seen as the favourite of his father’s four wives. Western diplomats believe the king has suffered for many years from a slow-onset form of vascular dementia; and MBS was the son he turned to for help.

Several diplomats recalled for us their meetings with MBS and his father. The prince would write notes on an iPad, then send them to his father’s iPad, as a way of prompting what he would say next.

“Inevitably I wondered whether MBS was typing out his lines for him,” recalls Lord Kim Darroch, National Security Adviser to David Cameron when he was British prime minister.

The prince was apparently so impatient for his father to become king that in 2014, he reportedly suggested killing the then-monarch – Abdullah, his uncle – with a poisoned ring, obtained from Russia.

“I don’t know for sure if he was just bragging, but we took it seriously,” says Jabri. The former senior security official says he has seen a secretly recorded surveillance video of MBS talking about the idea. “He was banned from court, from shaking hands with the king, for a considerable amount of time.”

In the event, the king died of natural causes, allowing his brother, Salman, to assume the throne in 2015. MBS was appointed Defence Minister and lost no time in going to war.

War in Yemen

Two months later, the prince led a Gulf coalition into war against the Houthi movement, which had seized control of much of western Yemen and which he saw as a proxy of Saudi Arabia’s regional rival Iran. It triggered a humanitarian disaster, with millions on the brink of famine.

“It wasn’t a clever decision,” says Sir John Jenkins, who was British ambassador just before the war began. “One senior American military commander told me they had been given 12 hours’ notice of the campaign, which is unheard of.”

The military campaign helped turn a little-known prince into a Saudi national hero. However, it was also the first of what even his friends believe have been several major mistakes.

A recurring pattern of behaviour was emerging: MBS’s tendency to jettison the traditionally slow and collegiate system of Saudi decision-making, preferring to act unpredictably or upon impulse; and refusing to kowtow to the US, or be treated as head of a backward client state.

Jabri goes much further, accusing MBS of forging his father the king’s signature on a royal decree committing ground troops.

Jabri says he discussed the Yemen war in the White House before it started; and that Susan Rice, President Obama’s National Security Advisor, warned him that the US would only support an air campaign.

However, Jabri claims MBS was so determined to press ahead in Yemen that he ignored the Americans.

“We were surprised that there was a royal decree to allow the ground interventions,” Jabri says. “He forged the signature of his dad for that royal decree. The king’s mental capacity was deteriorating.”

Jabri says his source for this allegation was “credible, reliable” and linked to the Ministry of Interior where he was chief of staff.

Jabri recalls the CIA station chief in Riyadh telling him how angry he was that MBS had ignored the Americans, adding that the invasion of Yemen should never have happened.

The former MI6 chief Sir John Sawers says that while he doesn’t know if MBS forged the documents, “it is clear that this was MBS’s decision to intervene militarily in Yemen. It wasn’t his father’s decision, although his father was carried along with it.”

We’ve discovered that MBS saw himself as an outsider from the very beginning – a young man with much to prove and a refusal to obey anybody’s rules other than his own.

Kirsten Fontenrose, who served on President Donald Trump’s National Security Council, says that when she read the CIA’s in-house psychological profile of the prince, she felt it missed the point.

“There were no prototypes to base him on,” she says. “He has had unlimited resources. He has never been told ‘no’. He is the first young leader to reflect a generation that, frankly, most of us in government are too old to understand.”

Making his own rules

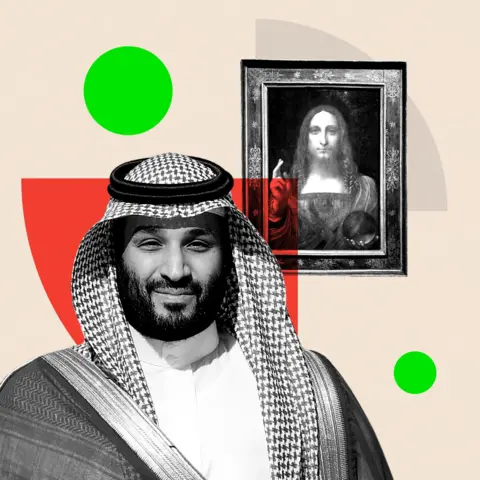

MBS’s purchase of a famous painting in 2017 tells us much about how he thinks, and his willingness to be a risk-taker, unafraid to be out of step with the religiously conservative society that he governs. And above all, determined to outplay the West in conspicuous displays of power.

In 2017, a Saudi prince reportedly acting for MBS spent $450m (£350m) on the Salvator Mundi, which remains the world’s most expensive work of art ever sold. The portrait, reputed to have been painted by Leonardo da Vinci, depicts Jesus Christ as master of heaven and Earth, the saviour of the world. For almost seven years, ever since the auction, it has completely disappeared.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBernard Haykel, a friend of the crown prince and Professor of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University, says that despite rumours that it hangs in the prince’s yacht or palace, the painting is actually in storage in Geneva and that MBS intends to hang it in a museum in the Saudi capital that has not yet been built.

“I want to build a very large museum in Riyadh,” Haykel quotes MBS as saying. “And I want an anchor object that will attract people, just like the Mona Lisa does.”

Similarly, his plans for sport reflect someone who is both hugely ambitious and unafraid to disrupt the status quo.

Saudi Arabia’s incredible spending spree on world-class sport – it is the sole bidder to host the FIFA World Cup in 2034, and has made multimillion-dollar investments in staging tournaments for tennis and golf – has been called “sportswashing”. But what we found is a leader who cares less about what the West thinks of him than he does about demonstrating the opposite: that he will do whatever he wants in the name of making himself and Saudi Arabia great.

“MBS is interested in building his own power as a leader,” says Sir John Sawers, the former Chief of MI6, who has met him. “And the only way he can do that is by building his country’s power. That’s what’s driving him.”

Jabri’s 40-year career as a Saudi official did not survive MBS’s consolidation of power. Chief of staff for the former Crown Prince Muhammed bin Nayef, he fled the kingdom as MBS was taking over, after being tipped off by a foreign intelligence service that he could be in danger. But Jabri says MBS texted him out of the blue, offering him his old job back.

“It was bait – and I didn’t bite,” Jabri says, convinced he would have been tortured, imprisoned or killed if he returned. As it was, his teenage children, Omar and Sarah, were detained and later jailed for money laundering and for trying to escape – charges that they deny. The United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention has called for their release.

“He planned for my assassination,” Jabri says. “He will not rest until he sees me dead, I have no doubt about that.”

Saudi officials have issued Interpol notices for Jabri’s extradition from Canada, without success. They claim he is wanted for corruption involving billions of dollars during his time at the interior ministry. However, he was given the rank of major-general and credited by the CIA and MI6 with helping to prevent al-Qaeda terrorist attacks.

Khashoggi’s killing

The killing of Jamal Khashoggi at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in 2018 implicates MBS in ways that are very hard to refute. The 15-strong hit squad was travelling on diplomatic passports and included several of MBS’s own bodyguards. Khashoggi’s body has never been found and is believed to have been hacked into pieces with a bone saw.

Professor Haykel exchanged WhatsApp messages with MBS not long after the murder. “I was asking, ‘how could this happen?’,” Haykel recalls. “I think he was in deep shock. He didn’t realise the reaction to this was going to be as deep.”

Dennis Ross met MBS shortly afterwards. “He said he didn’t do it and that it was a colossal blunder,” says Ross. “I certainly wanted to believe him, because I couldn’t believe that he could authorise something [like] that.”

Reuters

ReutersMBS has always denied knowledge of the plot, although in 2019 he said he took “responsibility” because the crime happened on his watch. A declassified US intelligence report released in February 2021 asserted that he was complicit in the killing of Khashoggi.

I asked those who know MBS personally whether he had learned from his mistakes; or whether having survived the Khashoggi affair, it had in fact emboldened him.

“He’s learned lessons the hard way,” says Professor Haykel, who says MBS resents the case being used as cudgel against him and his country, but that a killing like Khashoggi’s would not happen again.

Sir John Sawers cautiously agrees that the murder was a turning point. “I think he has learned some lessons. The personality, though, remains the same.”

His father, King Salman, is now aged 88. When he dies, MBS could rule Saudi Arabia for the next 50 years.

However, he has recently admitted he fears being assassinated, possibly as a consequence of his attempts to normalise Saudi-Israeli ties.

“I think there are lots of people who want to kill him,” says Professor Haykel, “and he knows it.”

Eternal vigilance is what keeps a man like MBS safe. It was what Saad al-Jabri observed at the beginning of the prince’s rise to power, when he pulled the telephone socket out of the wall before speaking to him in his palace.

MBS is still a man on a mission to modernise his country, in ways his predecessors would never have dared. But he’s also not the first autocrat who runs the risk of being so ruthless that nobody around him dares prevent him from making more mistakes.

Jonathan Rugman is consultant producer on The Kingdom: The world’s most powerful prince

Top picture: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.