Sven-Goran Eriksson, who has died aged 76, was the mild-mannered Swede with a surprisingly colourful private life who was the first foreign manager of the England national team.

Working with a so-called “golden generation” of players, he led England to the quarter-finals of three major tournaments in succession, including the World Cups of 2002 and 2006, in a five-year spell.

His reputation was forged largely in Italian football, chiefly in guiding Lazio to a Serie A and Coppa Italia double in 2000, but he also managed in his native Sweden, Portugal, Mexico, the Ivory Coast and China, among others, in a long coaching career.

He returned to England to manage at Manchester City and Leicester, as well as to take on an ill-fated role at Notts County, and his time in the country was also notable for the headlines he made off the field.

He sparked controversy in 2003 after being caught by paparazzi at a clandestine meeting with Chelsea’s billionaire owner Roman Abramovich, and three years later his England departure was in part hastened by unguarded comments to an undercover reporter suggesting he would be interested in taking over at Aston Villa.

Yet these were mere ripples compared to the media storms generated by lurid details of his affairs with TV personality Ulrika Jonsson and a Football Association secretary hitting the press. Remarkably, it transpired years later these trysts were just the tip of the iceberg.

Eriksson was born on February 5, 1948, in the home of his mother, Ulla, in the town of Sunne, Varmland, Sweden.

His father, also named Sven, was just 18 at the time and, having kept his girlfriend’s pregnancy secret from his parents, sneaked out of the house to attend the birth. There were also complications, with a doctor called after the umbilical cord wrapped the baby’s neck, but the child survived.

At the time Sven senior was a bus conductor and met Ulla, who worked in a textile store, on one of his routes. He later became a truck driver.

The pregnancy was unplanned. Sven senior did reveal all to his family soon after the birth but he did not move in with Ulla until they married some two years later.

That left Ulla, who came from a poor background and was initially shunned by Sven’s wealthier farming family, to fend for herself with the child, living in a small flat with no electricity or running water. Even after the marriage, the mother’s loneliness continued as Sven senior was sent away on military service.

“One day her son would show the world what she was never able to show herself,” wrote Eriksson, reflecting in later life on the tough hand his mother was dealt. “I was going to be her revenge on life.”

Eriksson, who was eight years older than his brother Lars-Erik, was conscientious at school but initially cast aside further education to pursue a job in insurance. He was a competitive junior ski jumper and also played ice hockey and skied cross-country as a child.

When weather permitted, football was his main sporting love, however. He played regularly as a full-back and, although he did not consider himself an outstanding player, he broke into the first team at nearby amateur side Torsby at the age of just 16 and became a regular.

Still playing as an amateur, he joined third division Sifhalla five years later when he quit his job to move to Amal to study economics.

After a year he moved on to play for Karlskoga when he became a PE teacher in Orebro and he later joined Vastra Frolunda, but his modest playing career was cut short through injury at the age of 27.

He moved into coaching at Degerfors in 1976 as assistant to his own future long-term number two Tord Grip, who had been his player-coach at Karlskoga. He took over as manager a year later after Grip left to become Sweden national team assistant boss and made an immediate impression, twice leading the team to the play-offs before promotion to the second division.

That brought him greater recognition, although his appointment by IFK Gothenburg in 1979 still came as a surprise.

“Here was this really shy man, who had been the manager of a little team called Degerfors, and now he was suddenly in charge of the biggest club in the country,” said defender Glenn Hysen. “We had never heard of him and it took us a while to respect him.”

Gothenburg lost their first three matches under Eriksson and he offered to quit but the players encouraged him to stay. His preference for 4-4-2 and zonal marking made the team hard to beat and they improved to finish second in the league and win the cup.

They finished runners-up again in 1981 and then really made a mark the following year as they won the domestic double and, against the odds, the UEFA Cup. Then in demand, Eriksson was snapped up by Benfica.

He won two Portuguese league titles and finished runners-up in the UEFA Cup before moving to Roma in 1984. After winning the Coppa Italia in 1986 he had a spell with Fiorentina before returning to Benfica, where he reached the European Cup final in 1990 and won another league title in 1991.

He won the Coppa Italia again with Sampdoria in 1994 and then, in 1996, came his first dalliance with English football as he agreed to take over at Blackburn. It was brief flirtation as he soon changed his mind and instead went to Lazio in 1997. It was there he really made his name, winning the Coppa Italia twice, the European Cup Winners’ Cup and Serie A.

It was this success that brought him to the attention of the FA after the sudden resignation of Kevin Keegan in 2000.

Naturally, hailing from overseas, his appointment was controversial but early impressions were hugely positive. He instantly turned around a stuttering World Cup qualifying campaign, the highlight of which was a remarkable 5-1 win over Germany in Munich.

From a seemingly impossible position when he took over, automatic qualification was secured with a memorable stoppage-time David Beckham equaliser in the final match against Greece at Old Trafford.

Beckham scored again as England claimed another famous win in the tournament itself, beating Argentina 1-0 in Japan, but their run ended in a 2-1 defeat to Brazil at the last-eight stage.

England had led after a superb opener from Michael Owen but, despite being reduced to 10 men, Brazil fought back. Ronaldinho scored the winner by catching goalkeeper David Seaman off-guard with a speculative free-kick.

Eriksson’s honeymoon was over and he learned how fierce English media critics could be. He was lambasted after losing a friendly 3-1 to Australia at Upton Park in February 2003, a game in which he changed his entire XI at half-time.

It was a precursor for the opprobrium which accompanied many bad results or performances.

“Whichever country you are, if you lose games you are criticised,” he reflected. “It’s only when it’s England it’s like a new world war.”

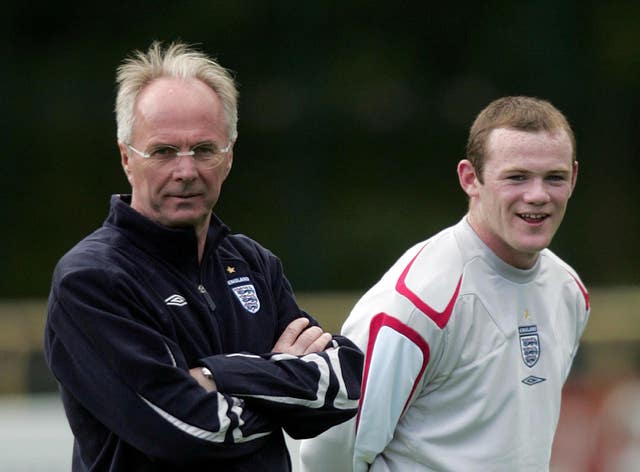

One good thing came from that Australia loss, however, was that a teenage Wayne Rooney, who would go on to become the country’s record goalscorer, was handed his debut by Eriksson.

With Rooney making waves, England looked a serious contender at Euro 2004 with a squad that also included Owen, Beckham, Paul Scholes, Steven Gerrard and Frank Lampard.

They conceded twice late on to lose the opener to France but Rooney shone as they beat Switzerland and Croatia to set up a quarter-final with Portugal. England made a dream start with an early Owen goal in that match in Lisbon but Rooney limped off later in the first half and they eventually went out 6-5 on penalties after a 2-2 draw.

There was a shock loss to Northern Ireland in qualifying for the 2006 World Cup but Eriksson led the team to the tournament in Germany, where history to some extent repeated itself.

After getting through the group stage and edging out Ecuador in the last 16, Portugal were again the quarter-final opponents. And again England were beaten on penalties, this time after Rooney was sent off.

Eriksson stepped down after the tournament, two years before the end of his contract, urging media not to make Rooney a scapegoat in his final press conference.

“He is the golden boy of English football, so don’t kill him,” the Swede pleaded.

In all, Eriksson managed England in 67 matches, 40 of which were competitive. He won 40 matches and lost 10.

Yet games alone do not tell the full story of Eriksson’s time in England. His private life proved a source of endless fascination to the media.

At the time he was involved in a relationship with Italian-British lawyer Nancy Dell’Olio. While this itself attracted plenty of publicity, it was little compared to that generated by Eriksson’s affair with fellow Swede Jonsson, who was at the height of her own fame.

After that storm died down, it later emerged Eriksson had also been involved with FA secretary Faria Alam, a story complicated by Alam’s further affair with another top FA employee. That was all that was known at the time but, in his autobiography in 2013, Eriksson admitted there were other lovers including a singer and former gymnast from Romania, and a Swede who worked for Scandinavian Airlines.

“To be the England manager you must win every game, not do anything in your private life and hopefully not earn too much money,” he later said of his time in the England hotseat and accompanying pressures.

After a year away, Eriksson returned to the game with Manchester City as part of a bold-looking new era following the takeover of former Thai prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra.

Hopes were high after a host of big-money signings and a bright start to the campaign but Thaksin grew impatient after a disappointing end to the season that culminated in an 8-1 loss to Middlesbrough.

Eriksson was sacked, against the wishes of fans, in the summer of 2008. With Thaksin himself selling up amid mounting debt to Sheikh Mansour just months later, Eriksson later conceded he joined City “one year too early”.

Eriksson then became something of a hired gun for the remainder of his career. He had a spell as Mexico national team manager and then took up a post as director of football at then League Two Notts County in 2009, lured by the apparent ambition of mysterious new owners. He quit after seven chaotic months which involved a surreal trip to North Korea and saw the club plunge towards financial collapse.

He took over as Ivory Coast manager for the 2010 World Cup but the African side failed to progress beyond the group stage. He spent a year in charge at Leicester, then in the Championship, from 2010-11 before later stints managing clubs in Thailand, the United Arab Emirates and China, and the Philippines national team.

He stepped down from his role as sporting director at Swedish club Karlstad in February 2023 due to health problems and revealed the following January he had been diagnosed with terminal cancer.

An outpouring of affection followed and, after revealing a hitherto unknown love of Liverpool, he was invited by the Merseyside club to manage a past players XI in a charity friendly at Anfield.

Eriksson spoke openly about his diagnosis and effectively said goodbye to the public in an emotional documentary about his life that was released in August 2024.

“I hope you will remember me as a positive guy trying to do everything he could do,” he said.

Eriksson leaves two children, Johan and Lina, from an earlier marriage to Anki Eriksson.