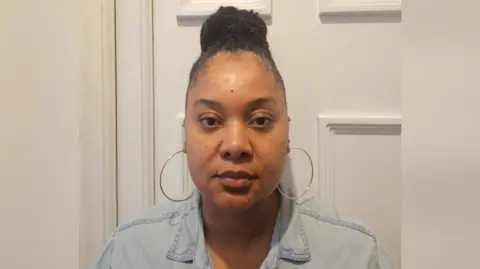

Pascalina Nellan

Pascalina NellanPeople with roots in the Chagos Islands have criticised what they called their “exclusion” from negotiations leading to the UK government’s deal to give up its sovereignty of the region.

The remote but strategically important cluster of islands in the Indian Ocean is set to be handed to Mauritius after more than half a century.

Some Chagossians the BBC spoke to broadly welcomed the deal, but many said indigenous people had been repeatedly refused an opportunity to take part in talks.

The Foreign Office said the interests of the Chagossian community had been “an important part of the negotiations”.

One of the largest islands on the tropical atoll, Diego Garcia, will remain a joint US-UK military base and is expected to remain so for 99 years with an option to renew.

Mauritius will be able to begin a programme of resettlement on the Chagos Islands, but not on Diego Garcia.

Pascalina Nellan, whose grandmother was born on the island before it turned into a home for navy ships and long-range bomber aircrafts, said the deal amounted to “backstabbing” by the UK government.

In recent years, the UK has faced rising diplomatic isolation over its claim to what it refers to as the British Indian Ocean Territory.

The International Court of Justice previously ruled the UK’s administration of the island, that some had called its “last colony in Africa”, was “unlawful” and must end.

The government of Mauritius has long argued that it was illegally forced to give the Chagos Islands away in return for its own independence from the UK in 1968.

Britain later apologised for forcibly removing more than 1,000 islanders from the entire archipelago between 1965 and 1973, and promised to hand the islands to Mauritius when they were no longer needed for strategic purposes.

Two years ago Ms Nellan moved to the UK, where she has been calling for Chagossian involvement in the deal over the territory.

Steeve Bancal

Steeve Bancal“Every time we made a request to be heard we have been excluded,” she said, claiming UK officials said the Chagossian community could not be involved in negotiations between the two countries.

“Today, again, we’ve been excluded,” the 34-year-old postgraduate student told the BBC.

“We need to respect the rights of indigenous people.”

Ms Nellan said she would like to go back to the islands, but not under Mauritius’ control.

“Our right to self-determination – whether we want to be British citizens or Mauritian citizens at all – has been stripped today,” she said.

Frankie Bontemps, a second generation Chagossian in the UK, told the BBC that he felt “betrayed” and “angry” on Thursday because “Chagossians have never been involved” in the negotiations.

“We remain powerless and voiceless in determining our own future”, he said and called for the full inclusion of Chagossians in drafting the treaty.

Isabelle Charlot

Isabelle CharlotSteeve Bancal, a trainee social worker from Sussex, was positive about the deal.

He said Mauritius was more likely to put resettlement plans in place for Chagossians than the UK, which had “done nothing” for the community.

He expressed hope to return to the islands with his mother, who was also removed from Diego Garcia. She resettled in Mauritius, where Mr Bancal was born.

Mr Bancal said it would be a “dream come true” for his mother, 74, to return to Diego Garcia.

However, he also criticised the negotiations, saying they happened “behind closed doors”.

“None of us were told what was happening. It’s unfair on us,” he said.

“It’s our heritage – we should have had one or two people in the room.

“I don’t think the UK government trusts us.”

Isabelle Charlot was born in Mauritius to Chagossian parents, and has lived in the UK – where she is the chairperson of the Chagos Islanders Movement – for 19 years.

She said she now hoped to return to the archipelago.

“That is what my family and I have been waiting for,” Ms Charlot told the BBC.

She said she welcomed the deal as a step toward “reclaiming [her] identity, heritage and homeland”, all of which had been “robbed” from her.

“I [knew] that the Labour government would want to right the historical wrongs and respect the international law,” she said.

‘Genuinely historic’

Some Conservative leadership candidates suggested the deal could undermine UK security.

Robert Jenrick said: “It’s taken three months for Starmer to surrender Britain’s strategic interests.”

Former foreign secretary James Cleverly described the move as “weak, weak, weak”, while former security minister Tom Tugendhat suggested it risked allowing China to gain a military foothold in the Indian Ocean.

However Jonathan Powell, the prime minister’s special envoy for negotiations between the UK and Mauritius, dismissed such criticism of the deal and said Mr Cleverly had previously been leading the talks.

Human Rights Watch called for the Chagossians to be consulted on the deal.

Clive Baldwin, senior legal advisor at the organisation, said the deal did not “guarantee that the Chagossians could return to their homeland”, and “appears to explicitly ban them from the largest island, Diego Garcia, for another century”. He called for reparations for those who were displaced.

Mr Baldwin called for meaningful consultations with the Chagossians.

He said unless this happened, the UK, US and now Mauritius would be responsible for “a still ongoing colonial crime”.

ALAMY

ALAMYPowell said on Thursday that Britain’s past treatment of the Chagossians was “shameful”.

But he called the agreement, reached after 11 rounds of negotiations, “genuinely historic”.

He said he could not guarantee whether Chagossians would be able to return to the islands, since they were to become Mauritian territory, but that the UK was committed to “help with resettlements if that’s possible”.

The UK government said it would also provide a package of financial support to Mauritius, including annual payments and infrastructure investment.

A Foreign Office spokesperson said: “This is a bilateral agreement between the UK and Mauritius.

“We are mindful that the future of the islands is an important issue for the Chagossian community. Their interests have been an important part of the negotiations.”