Planet Labs

Planet LabsWestern technology and finance are helping Ukraine carry out hundreds of long-range strikes inside Russia.

That is despite Nato allies still refusing to give Ukraine permission to use Western-supplied munitions to do so – mostly because of fears of escalation.

Ukraine has been stepping up its long-range strikes inside Russia over the past few months, launching scores of drones simultaneously at strategic targets several times a week.

The targets include air force bases, oil and ammunition depots and command centres.

Ukrainian firms are now producing hundreds of armed one-way attack drones a month, at a fraction of the cost it takes to produce a similar drone in the West.

One company told the BBC it was already creating a disproportionate impact on Russia’s war economy at a relatively small expense.

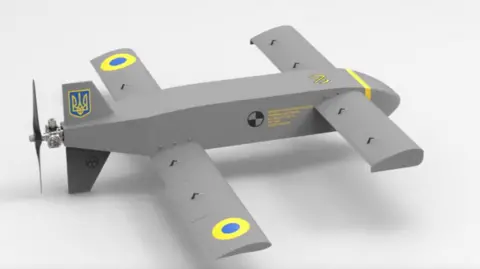

Terminal Autonomy

Terminal AutonomyThe BBC has been briefed by a number of those involved in these missions. They include one of Ukraine’s largest one-way attack drone manufacturers, as well as a big data company which has helped develop software for Ukraine to carry out these strikes.

Francisco Serra-Martins says the strategy is already creating huge dilemmas for Moscow. He believes that with extra investment, it will turn the tide of the war in Ukraine’s favour.

Eighteen months ago, the company he co-founded, Terminal Autonomy, didn’t even exist. It is now producing more than a hundred AQ400 Scythe long-range drones a month, with a range of 750km (465 miles). The company also makes hundreds of shorter range AQ100 Bayonet drones a month, which can fly a few hundred kilometres.

The drones are made of wood and are being assembled in former furniture factories in Ukraine.

Mr Serra-Martins, a former Australian Army Royal Engineer, set up the company with his Ukrainian co-founder, backed by US finance. It is one of at least three companies now producing drones in Ukraine at scale.

He describes his drones as “basically flying furniture – we assemble it like Ikea”.

It takes about an hour to build the fuselage and half that time to put the brains inside it – the electronics, motor and explosives.

The company’s Bayonet drone costs a few thousand dollars. In contrast, a Russian air defence missile used to shoot it down can cost more than $1m.

Terminal Autonomy

Terminal AutonomyIt is not only cheap drones making the difference.

Palantir, a large US data analysis company, was one of the first Western tech companies to aid Ukraine’s war effort. It started by providing software to improve the speed and accuracy of its artillery strikes. Now it has given Ukraine new tools to plan its long-range drone strikes.

British engineers from Palantir, working with Ukrainian counterparts, have designed a programme to generate and map the best ways to reach a target. Palantir makes clear it is not involved in the missions, but has helped train more than 1,000 Ukrainians how to use its software.

The BBC has been shown how it works in principle. Using streams of data, it can map Russia’s air defences, radar and electronic jammers. The end product looks similar to a topographical chart.

The tighter the contours, the heavier the air defences. The locations have already been identified by Ukraine using commercial satellite imagery and signals intelligence.

Louis Mosley of Palantir says the programme is helping Ukraine to skirt around Russia’s electronic warfare and air defence systems to reach their target.

“Understanding and visualising what that looks like across the entire battle space is really critical to optimising these missions,” he says.

The execution of the long-range drone strikes is being co-ordinated by Ukraine’s intelligence agencies, who work in secrecy. But the BBC has been told by other sources about some of the detail.

Scores of drones can be fired for any one mission – as many as 60 at one target.

EPA

EPAThe attacks are mostly carried out at night. Most will be shot down. As few as 10% may reach the target. Some drones are even shot down along the way by friendly fire – Ukraine’s own air defences.

Ukraine has had to work out ways to counter Russian electronic jamming. Terminal Autonomy’s Scythe drone uses visual positioning – navigating its course and examining the terrain by Artificial Intelligence. There is no pilot involved.

Palantir software will have already mapped the best routes. Mr Serra-Martins says flying a lot of drones is key to overwhelming and exhausting Russia’s air defences. So too is making the drones cheaper than the missiles trying to shoot them down, or the targets they are trying to hit.

Prof Justin Bronk of the Royal United Services Institute says Ukraine’s long-range drone attacks are creating dilemmas for Moscow. Although Russia has a lot of air defences, it still cannot protect everything.

Prof Bronk says Ukraine’s long-range strikes are showing ordinary Russians that “the state can’t defend them fully and that Russia is vulnerable”.

Ukrainian drones have been spotted more than 1,000km (620 miles) inside Russia. They have been shot down over Moscow.

But the focus has been on military sites. The map below highlights just a handful of the dozen targets hit over the past few months. They include five Russian airbases.

Prof Justin Bronk says targeting Russian airbases has so far been the only effective way Ukraine has to respond to Russia’s glide bombs.

It has forced Russia to move aircraft to bases further away and reduce the frequency of their attacks. Satellite imagery shows how Ukrainian drones have successfully damaged hangars at its Marinovka airbase.

Ukraine clearly believes it could do even more with the help of Western-made long-range weapons. But so far, allies have rejected Kyiv’s pleas.

There is still a lingering fear, especially in Washington and Berlin, that it could drag the West further into the conflict. But that hasn’t stopped Western companies and finance from helping Ukraine.

Ukraine is still largely having to rely on its home-grown efforts, convinced that bringing the war to Russia is a key to winning this war.

Francisco Serra-Martins also believes Western manufacturers are still “woefully unprepared” to fight high-intensity warfare – producing far fewer long-range weapons at a much higher cost. He says what Ukraine really needs now “is a lot of good enough systems”.

The BBC has talked to one Ukrainian company which is already developing a new cruise missile, at least 10 times cheaper than a British-made Storm Shadow missile.

Despite the West’s misgivings, Ukraine is planning to step up its attacks on Russia. Mr Serra-Martins says: “What you’re seeing now is like nothing compared to what you’ll see by the end of the year.”