BBC

BBCA repeating tone – blip, blip, blip – is the audible reminder that we are in one of the most hazardous nuclear sites in the world: Sellafield.

That sound – pulsing from speakers inside the cavernous fuel-handling plant – is a signal that everything is functioning as it should.

That is comforting because Sellafield, in Cumbria, is the temporary home to the vast majority of the UK’s radioactive nuclear waste, as well as the world’s largest stockpile of plutonium.

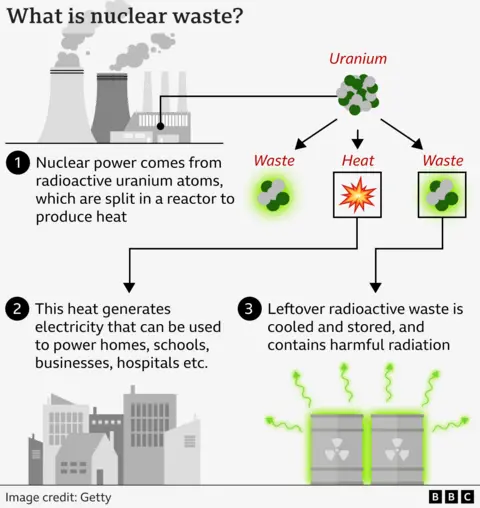

That waste is the product of reactions that drive the UK’s nuclear power stations and it is highly radioactive.

It releases energy that can penetrate and damage the cells in our bodies, and “it remains hazardous for 100,000 years”, explains Claire Corkhill, professor of radioactive waste management at University of Bristol.

Sellafield is filling up – and experts say we have no choice but to find somewhere new to keep this material safe.

Nuclear power is also part of the government’s stated mission for ”clean power by 2030”. More nuclear power means more nuclear waste.

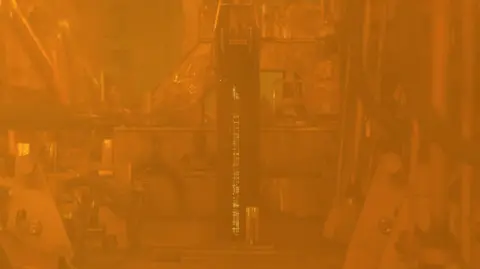

Inside Sellafield’s fuel-handling plant, we watch from behind one metre-thick, lead-lined glass as operators remotely control robotic arms.

They manoeuvre joysticks on what look like large retro game-controllers, as the arms pull used nuclear fuel rods – still glowing hot and highly radioactive – from the heavy metal containers in which they arrived.

This complex operation never stops. Sellafield runs 24 hours a day with 11,000 staff. It costs more than £2bn per year to keep the site going, and it comprises more than 1,000 buildings, connected by 25 miles of road.

However, in recent years, doubts have been raised about the site’s security and physical integrity.

One of its oldest waste storage silos is currently leaking radioactive liquid into the ground. That is a “recurrence of a historic leak” that Sellafield Ltd, the company that operates the site, says first started in the 1970s.

Sellafield has also faced questions about its working culture and adherence to safety rules. The company is currently awaiting sentencing after it pleaded guilty, in June, to charges related to cyber-security failings.

An investigation by the Guardian revealed that the site’s systems had been hacked, although the Office for Nuclear Regulation said there was “no evidence that any vulnerabilities had been exploited” by the hackers.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAll of this has cast a shadow over an operation that, as well as taking in newly created nuclear waste, also houses several decades worth of much older radioactive material.

The site no longer produces or reprocesses any nuclear material, but this is where the race began to produce plutonium for nuclear weapons at the height of the Cold War.

“It was the dawn of the nuclear age,” says Roddy Miller, Sellafield’s operations director. “But because it was a race, not a lot of thought was given to the long-term safe storage of the waste materials that were produced.”

The leaking storage silo, which was built in the 1960s, is just one of the buildings that now has to be emptied so the material inside can go into more modern silos. The building was only ever designed to be filled, and Sellafield says its plans to clear the site and demolish the building are the safest option.

The site’s head of retrievals, Alyson Armett, points out that without a “permanent solution” for the nuclear waste, the plans to decommission could be delayed.

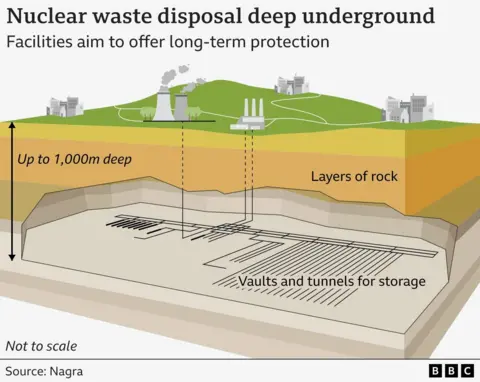

The current plan for that permanent solution is to bury the waste deep underground.

A complicated search – both scientifically and politically – is currently on for somewhere to lock it away from humanity permanently.

“We need to isolate it from future populations or even civilisations, that’s the timescale we’re looking at,” says Prof Corkhill.

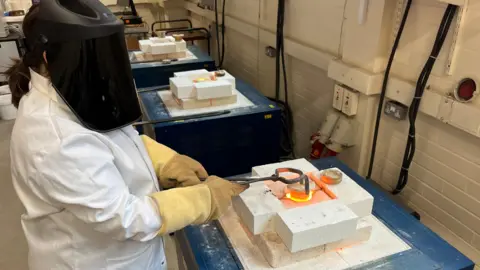

She studies how radioactive waste material can be made safe for extremely long-term storage, and is searching for the most stable, inert substance that nuclear waste could be “baked into”.

“We turn it into a solid – glass, ceramic or a material that’s just like the rocks that the uranium originally came from,” she explains. At Sellafield, the highest level of radioactive waste is stabilised in a similar way before it is stored on-site.

The plan for permanent, underground storage is to contain that solid waste in a Russian doll-like series of barriers. The glass, encased in steel, will be shielded in concrete, then buried beneath the Earth‘s own barriers – layers of solid rock.

The question is, where will that facility be?

‘The waste is already here’

Six years ago, communities in England and Wales were asked to come forward if they were willing to consider having a disposal facility built near their town or village.

Potential sites will need the ideal geology – enough solid rock to create that permanent barrier. However, they also need something that might be more difficult – a willing community.

There are financial incentives for communities to take part in this discussion. So far, five have come forward. Two have already been ruled out. Allerdale in Cumbria was deemed unsuitable because there was not enough solid bedrock. Then, in September, councillors in South Holderness, in Yorkshire, withdrew after a series of local protests.

Government scientists are assessing the remaining three communities that are currently in the running. Geologists have been carrying out seismic testing – looking for that all-important impermeable rock.

One of the communities being considered is very close to the Sellafield site in West Cumbria, at Seascale.

Local councillor David Moore says the industrial complex is “just down the road, and it’s the biggest employer in the area”.

He adds: “I think that’s why conversation here’s different. We’re already the hosts of the waste. And we all want to find it a safer location.

“I have seven grandchildren who live in this community, and I want them to live in a safe environment.”

It is not yet clear if Mid Copeland, the area under consideration that includes Seascale, will have the right rock. The survey and consultation here – and in the other locations being considered – are in their early stages and scheduled to last at least a decade.

In the meantime, the conversation goes on and each community being considered for a geological disposal facility (GDF) now receives about £1m a year in investment while initial scientific tests are carried out.

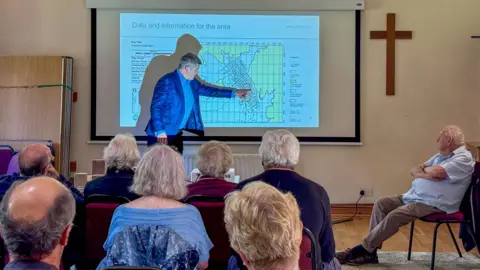

Mr Moore is part of a committee called a GDF partnership. It includes local residents, local government and representatives of Nuclear Waste Services, which is the government body behind this project.

These partnerships aim to keep the process transparent and ensure local people are well-informed. They also decide how the money is spent.

If a GDF is built here, Mr Moore says, there will be billions of pounds invested in the area. “If we’re going to host this on behalf of the UK, the community should benefit,” he says.

Also still on the shortlist are South Copeland, again on the Cumbrian coast, and a site on the east coast in Lincolnshire, where there have been a number of peaceful, but angry, protests.

On Halloween 2021 in Theddlethorpe, one of the local villages, several residents used their gardens to put up garish anti-nuclear dump scarecrows, inspired by an idea from pressure group the Guardians of the East Coast, which is campaigning against the disposal facility.

Ken Smith, from nearby Mablethorpe, is a member of both the campaign group and the local GDF partnership.

He thinks the government’s approach to finding a nuclear waste disposal site “stinks”.

Mr Smith is concerned that the voices of those most affected might not be heard and says it is unclear how local opinion will be measured at the end of the consultation.

The Department for Energy Security and Net Zero says a GDF will provide “safe and long-term disposal of the most hazardous radioactive waste”.

Prof Corkhill is convinced that a GDF is the safest solution. “We extract uranium from the rocks in the ground, we get energy from them and [this disposal facility essentially means] they’re returned back to the ground again,” she says.

“That uranium has been present in those rocks for billions of years. It’s been pushed and pulled, squeezed and heated, exposed to water and air. But the uranium is still safely locked up.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn Finland, a facility, called Onkalo, has already been built, and could receive its first nuclear waste within the next year.

Locations for three other sites around the world have also been chosen, in Switzerland, Sweden and France. They are at various stages of development.

In the UK, the search, studies and consultations continue. Only when those have been concluded and some kind of final assessment of community support, like a referendum, has taken place will construction of a GDF begin. The earliest that any waste could be put inside it is estimated to be during the 2050s.

Until then, it will continue to be stored and managed at Sellafield.

“We’ve benefited from nuclear energy in this country for 70 years, but we are still a long way behind cleaning up the legacy that has been left behind,” says Prof Corkhill.

“When we move to thinking about a new generation of nuclear power, we need to think about the waste now.”